March 16th 2023

Introduction

Should we be property dualists? This is a very difficult question to answer not only because there are so many complex arguments for and against, but because the question itself is enigmatic. The question is not something like, “Between property dualism and physicalism, or even against substance dualism, which thesis is better supported?”. It is also not “Which thesis do you, the answerer and writer of this essay, subscribe to?”. No, I think this question to be a much more interesting one than that. It is a question of “ought”, a question of “should”. And when philosophical musing crosses the “is/ought” line things can get very sticky and very, very interesting.

In order to attempt to answer this question I will first briefly go over what property dualism is and what some of the arguments for it are. I will then do the same for some opposing theories. Next, I will elaborate on a few of the small and large scale potential outcomes of holding these positions to try to determine which may be the most advantageous if widely adopted. This will include discussions regarding the benefits of epistemological anarchy as espoused by people like Feyerabend as well as the process of the dialectic on a large scale along with my own conceptualization of the computational power of humanity as one machine as contrasted with the individual. In conclusion, I will reiterate my overall answer to this question which is that while I myself am a physicalist and believe in the validity of physicalism, I also believe a non-zero number of people should be property dualists.

Property Dualism, an Introduction

What is property dualism, and what are some of the arguments for it? “[P]roperty dualism says that there are two essentially different kinds of property out in the world. …Genuine property dualism occurs when, even at the individual level, the ontology of physics is not sufficient to constitute what is there. The irreducible language is not just another way of describing what there is, it requires that there be something more there than was allowed for in the initial ontology.” (Robinson. 2023) This basically means that proponents of this theory deny materialism and reductionism as full and sufficient explanations of consciousness. Some of these more modern proponents include David Chalmers, Saul Kripke, and Thomas Nagel (Nagel not being a full supporter, but having a distrust of physicalism and having laid a foundation built upon later by Chalmers regarding subjective experience or “something it is like to be”). There are several arguments for their position including Mary and her color vision, Philosophical Zombies, and The Chinese Room (Chinese room being more specific to the potential implications of materialism i.e. artificial intelligence), among others. In this paper we will focus on and discuss in more detail specifically exactly what The Explanatory Gap and The Hard Problem of Consciousness are and how those issues are countered by physicalists.

The Opposing Theories

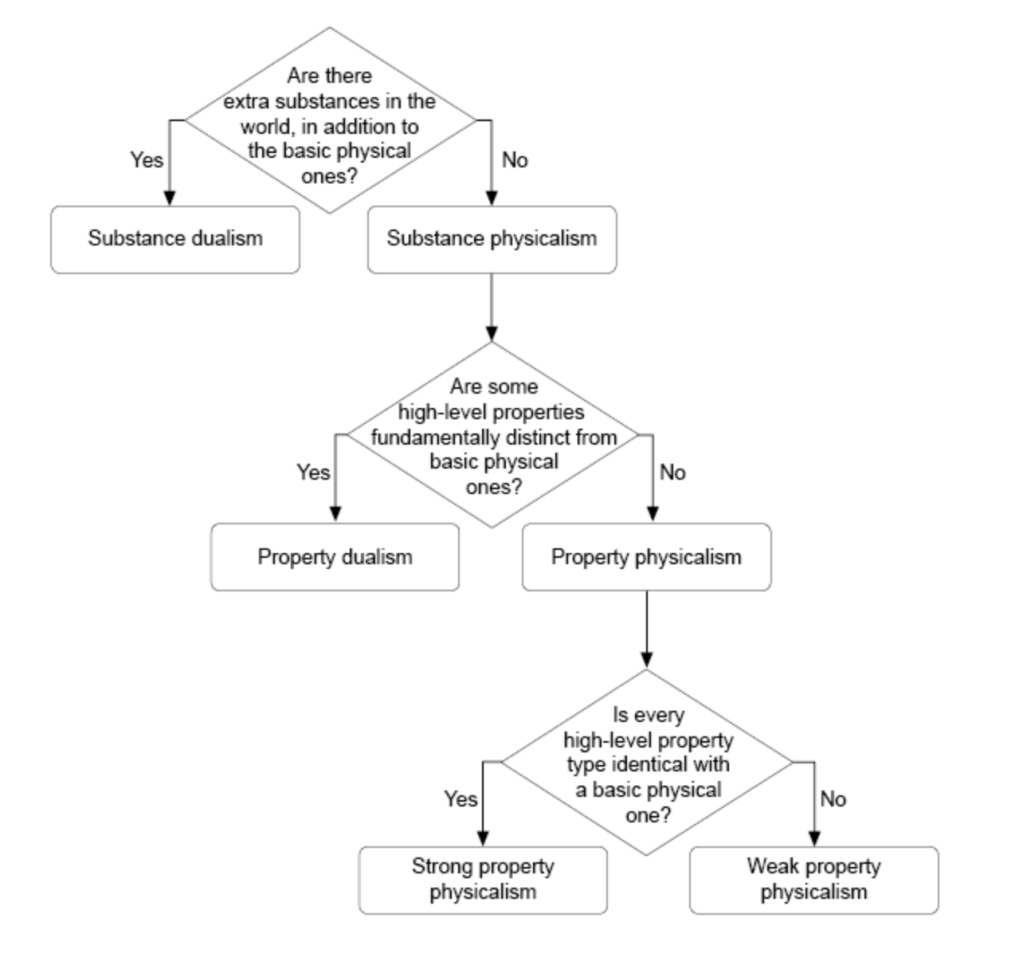

There are several theories in opposition to property dualism, one being substance dualism which is a more drastic stance that was taken by Renes Descartes and can be found in many religious traditions. This is the position that, as illustrated in the diagram below, there are two completely different substances making up the world. This second substance could be something like a soul. This theory is not as widely regarded in the philosophical or scientific community today, so we are going to focus more of our time on the broad category of physicalism within which there are several competing theories. It is important to note these do not cover all potential theories out there, supervenience, conscious realism, panpsychism, and idealism are some of many branches of and/or different theories out there that we will not cover in this paper, although my final thesis statement applies to them as well and I am partial to the conscious realism of Donald Hoffman myself.

Varieties of dualism and physicalism. Figure 3

We will now break down The Hard Problem as posited by David Chalmers. According to Chalmers, The Hard Problem relates to why qualia exist. He believes that even if we answer all of the so called “easy problems” and explain how qualia come to be, we will not have explained why there is “something it is like to be” that creature. His zombie thought experiment being an extension of this, arguably showing that a creature without qualia is conceivable and therefore possible. Physicalist Daniel Dennett disagrees. He is a materialist and reductionist but not what he calls a “greedy reductionist”. He believes everything can be explained by lower levels, although it is not always practical to do so. Dennet dismisses the Hard Problem as an illusion, basically stating that once all the “easy problems” are solved there will be nothing else left. Consciousness as a phenomenon doesn’t exist on its own. (Dennett & Weiner. 2007) This is known as eliminative materialism. Dennett also counters the zombie thought experiment with his own Zimboes, which question the validity of Chalmers’ assertion of conceivability.

Next, we will cover the Explanatory Gap. Joseph Lavine first proposed the idea of the Explanatory Gap and it is similar to, and may have inspired, Chalmers’ Hard Problem. It speaks to the supposed gap between what natural sciences can explain and phenomenal experiences, which appear to be distinct and inexplicable through purely physical means. He asserts there is a distinction between metaphysical and epistemological claims. (Lavine. 2001) Papinuau’s answer to Lavine’s argument is the Intuition of Distinctness which he describes thusly “There is a sense in which material concepts do “leave out” the feelings. They do not use the experiences in question–they do not activate them, by contrast with phenomenal concepts, which do activate the experiences. But it simply does not follow that material concepts “leave out” the feelings in the sense of failing to mention them. They can still refer to the feelings, even though they don’t activate them.” (Papineau. 2002) The way I understand this quotation is similar to describing the workings of a record player vs. playing music on it. The music still comes from the record itself, as sound waves, but you can’t just describe every detail of how a record player works and have the music magically appear. You have to actually “play” the device. In analogy, in order to have an experience you have to “play” the physical elements in the proper way to produce the conscious experience, not just describe how they come about. The fact that there is a difference between description and activation does not mean they are distinct from the physical basis nor that they cant be understood in physical terms. There are many more nuances within this debate but for the sake of this essay we will end this portion here.

The Case for Contrarianism

Now on to the broader question: what if you had a magic wand and could convince everyone to believe the side of this debate that you deemed correct? What would the results of this be? What are some of the pros and cons to having a belief in any of these at both the individual and societal levels. Does believing in one or the other theory lead to better results, more useful research, or even more ethical behaviors? Will one lead to technological or medical breakthroughs or “butterfly effect” us into oblivion? These are just some of the questions to consider when prescribing behavior. Describing the state of research on a topic is relatively easier, but jumping the “is/ought” gap is more difficult. David Hume articulates this issue in book III, part I, section I of A Treatise of Human Nature. He is of the opinion that we must be wary of making the jump between the two but many schools of philosophy and specifically ethics have been created in order to attempt to do just that. One type is utilitarian ethics, whereby equations with varying levels of complexity have been considered to attempt to take all potential effects into account when prescribing an “ought”. The main tenant of this type of theory being that what one “ought” to do is what creates the most beneficial results. But as I hinted at with the questions beginning this section, some of those questions are well outside our human understanding and reasoning abilities. We would need knowledge of the future and computation of so many variables as to be impossible.

The one thing that can approximate this computational power, at least to the greatest extent currently possible, is the computational power of the entirety of humanity. This can be likened to the movement of the dialectic. The individual person is limited in their abilities and confined by perspectivism as described by Nietzsche. The entirety of humanity, on the contrary, has much larger data storage and computational power. This has been illustrated in many forms, one being the jelly bean problem. In basic terms, “If one asks a large enough number of people to guess the number of jelly beans in a jar, the averaged answer is likely to be very close to the correct number. True, occasionally someone may guess closer to the true number. But as you repeat the experiment, the same person never is better every time – the crowd is smarter than any individual”. (Surowiecki. 2014) According to Surowiecki in his book The Wisdom of Crowds, there are 4 things needed in order for this computational aggregation of the data of crowds to function. They are:

- Diversity of Opinion- Members have private information

- Independence- Members do not form consensus and eschew influence

- Decentralization- Members are able to specialize

- Aggregation- Some method exists for turning these private judgements into a collective decision

One example of this functioning was with the stock market style program called Future Map which was a DARPA project able to predict political and social events with spooky accuracy. This program was shot down by congress on ethical grounds.

So how does this wisdom of crowds relate to this, or any, philosophical question? I myself am an epistemological anarchist in the school of Paul Feyerabend. I believe, as he does, that there are benefits to allowing or encouraging even somewhat illogical or improbable theories as you never really know what will pan out. Due to our own perspectivism and limitations, as well as the constraints of scientific paradigms, which as we saw with the Copernican revolution are not always correct and can hold back advancement until they are overturned, we can often miss important discoveries due to our own biases, limitations, and drive for consensus. Now this isn’t to say I think we should hold all theories in high regard or to equal levels, obviously some are much more credible than others. But the dialectic feeds on contradictions and opposition and the computational power of humanity plus time will yield a much better result than one person deciding or even the scientific or philosophical consensus of a given period. I think we should build a system within academia that facilitates this dialectical movement with Surowiecki’s 4 requirements as a foundation.

Conclusion

This leads me to the position that, while I am partial to the arguments towards physicalism, asking what beliefs I would prescribe for the others is a much more difficult task. My conclusion is that some non-zero amount of people should be property dualists in order to enhance the dialectic. One person’s computational thought power alone is unable to consider all aspects of an issue nor potential future effects/outcomes, and is no comparison to the computational power of humanity when members adhere to Surowiecki’s 4 conditions. So, while I believe the arguments and theories of physicalism hold more weight and are more scientifically supported, I would not cross the is/ought gap and prescribe this for everyone.

Bibliography

Dennett D. (1995) ‘The unimagined preposterousness of zombies’, Journal of Consciousness Studies, vol. 2, no. 4, pp. 322–6.

Dennett, D. C., & Weiner, P. (2007). Consciousness explained. Little, Brown and Company.

Feyerabend, Paul. Against Method. London: Verso, 2010.

Hofstadter, Douglas R. Godel, Escher, Bach. London: Penguin, 2000.

Hofstadter, Douglas R. I Am A Strange Loop. BasicBooks, 2008.

Kim, J. (2002) ‘Précis of Mind in a Physical World’, Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, vol. 65, no. 3, pp. 640–3.

Levine, J. (2001) Purple Haze: The Puzzle of Consciousness, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Papineau, D. (2002) Thinking About Consciousness, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

Robinson, Howard, “Dualism”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2023 Edition), Edward N. Zalta & Uri Nodelman (eds.), forthcoming URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2023/entries/dualism/>.

Solms, Mark. Hidden Spring: A Journey to the Source of Consciousness. S.l.: W W Norton, 2022.

Surowiecki, James. The Wisdom of Crowds: Why the Many Are Smarter than the Few. London: Abacus, 2014.