Between Nietzsche’s critiques of free will/transparency of self, and his idea of what constitutes great men appears a fun spot to slide memetics in. His description runs contrary to purely evolutionary interests/the will to life. He discusses how all great philosophers are unmarried. He praises a solitary life and the use of suffering as motivator for greatness. It’s funny because the drive to become great is usually linked to evolutionary fitness with regards to obtaining resources and access to mates (thus passing on genes) but Nietzsche just wants the will to power without the fruits that would come with it.

Considering his critique of free will this would basically mean either a dysgenic corruption of the will to life or a memetic hijacking since the body is just a conduit for whichever drive/or algorithm is steering. This would run completly contrary to a eugenic worldview. Another instance of proof for people mislabeling Nietzsche as nazi inspiration. But instead of a will to power being an offshoot of memetic selection, more likely I think it’s cope. I think one wishes to believe in pure intentions for greatness while the will to life is secretly positioning you to get more bitches.

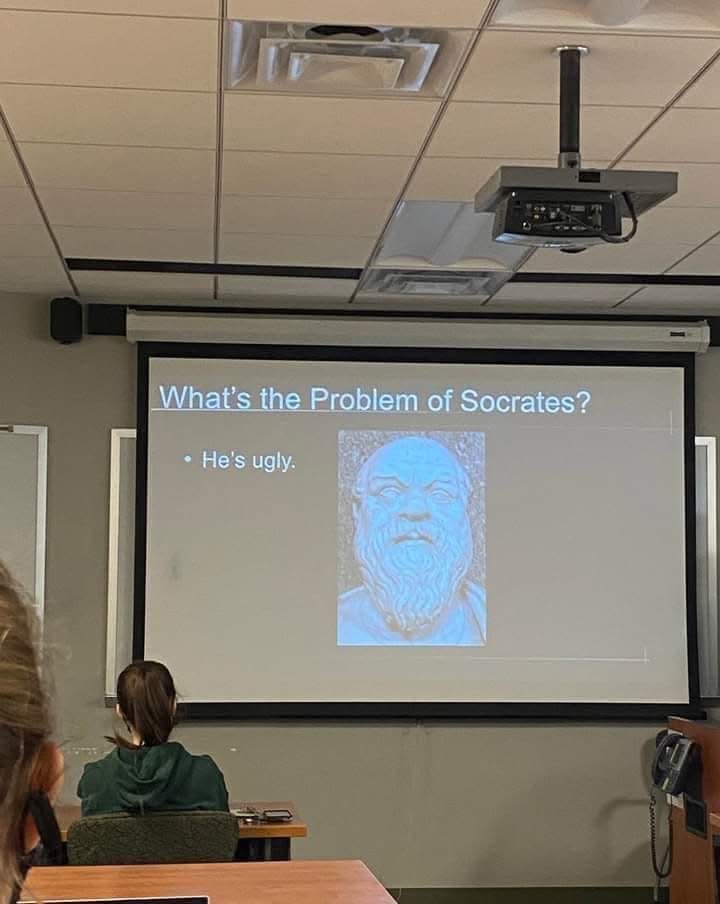

Literally Nietzsche

Key critiques Nietzsche had of Socrates:

- Overemphasis on Rationality: Nietzsche believed Socrates’ focus on reason and dialectics undermined instinctual, life-affirming values, replacing them with abstract rationality that negated the body and its drives.

- Resentment of Life: Nietzsche saw Socrates as a symptom of decline, arguing that his philosophy emerged from a deep dissatisfaction with life, a kind of revenge against existence.

- Moral Dogmatism: Nietzsche criticized Socrates for introducing a rigid moral framework that suppressed individuality and subjective values in favor of universal, objective principles.

- Ugly and Decadent: Nietzsche even took aim at Socrates’ physical appearance, which he saw as reflective of his inner decadence and as a sign of a decaying culture.

- Turn Away from Tragedy: Nietzsche viewed Socrates as the destroyer of Greek tragedy, replacing the Dionysian and Apollonian balance with a purely rational, anti-aesthetic worldview.

A random question and my answer to it:

“If Nietzsche was the visionary that some of you agrees to, why are there no movements operating in his name? I’m not asking to be some sort of troll. I earnestly value Nietzsche’s work myself. I just find it a bit disappointing that his work has become more about debate than it is about action and change. Is he practical? Or is he merely theoretical? Or worse, fantastical, like some longed for Utopia or Paradise? All I can ever find are those who “DISCUSS” Nietzsche. How is he made practical?”

Nietzsche would have scoffed at the idea of a movement operating in his name. His philosophy is fundamentally opposed to the very notion of rigid schools or movements, which he saw as stifling individuality and enforcing dogmatic adherence to collective ideals. A Nietzschean “movement” would be an oxymoron, directly contrary to his advocacy for self-overcoming and self-fulfillment. He was deeply skeptical of herd mentalities, even within intellectual circles, and warned against reducing profound ideas to simplistic slogans or group identities.

His work is profoundly descriptive rather than prescriptive. He diagnosed the condition of modernity—a world increasingly devoid of theistic meaning—and foretold the rise of nihilism and the challenges it would pose. In this sense, Nietzsche was remarkably accurate, arguably prophetic, as postmodernism and existentialist thought have wrestled with the very issues he identified: how to create meaning in a non-theistic, fragmented world. He wasn’t offering blueprints for utopias or systems for collective change but instead urging individuals to confront and transcend these conditions themselves.

What Nietzsche offers prescriptively is deliberately elusive and individualized. Concepts like the Übermensch or the “child” in his metaphor from Thus Spoke Zarathustra are not universal archetypes to be followed but deeply personal goals for self-overcoming. Importantly, the Übermensch wouldn’t be recognized as such by others. By definition, they stand outside the norms and values of their time, creating their own values rather than conforming to existing ones. Their transformation is internal, not something validated by collective acknowledgment or movements.

The fact that Nietzsche’s philosophy is debated rather than acted upon might actually affirm his insight. His work resists commodification or direct application because it challenges each individual to forge their own path, a process that defies collective action or mass appeal. In this sense, Nietzsche’s legacy is less about creating movements and more about planting seeds of radical self-reflection and critique that influence individuals on an intensely personal level. That might feel less satisfying to those seeking immediate “action and change,” but it’s perfectly consistent with the nature of his thought.

Furthermore:

This kind of question highlights why understanding historical context is absolutely essential when evaluating a thinker like Nietzsche—or any figure whose ideas have become foundational. It’s similar to the way people dismiss Freud, mocking him for his outdated theories, cocaine use, and provocative concepts like penis envy, while completely missing the seismic shifts he brought to the field of psychology. Freud’s work, flawed and dated as parts of it are, introduced and normalized the idea of the unconscious, a concept so integral to modern psychology that we barely think to question it anymore. His contributions laid the groundwork for fields like cognitive behavioral therapy, even if we’ve refined, built on, and discarded many of his original ideas. That evolution isn’t a flaw; it’s the mark of a profound contribution.

The same applies to Nietzsche. Without understanding his historical context, it’s easy to overlook the fact that much of existentialism and postmodernism—movements that have defined modern philosophy—stemmed from challenges he was among the first to identify. Nietzsche’s work isn’t shocking or revelatory to us now precisely because his insights have been absorbed into the cultural and intellectual framework of the modern world. Concepts like the death of God, nihilism, and the struggle to create meaning in a secular world feel obvious to us today because we’ve inherited his foresight. The very fact that his ideas seem commonplace now is evidence of how deeply influential he was, not a reason to dismiss him. If anything, such questions reveal the risk of failing to appreciate how ideas we take for granted often originate from groundbreaking thinkers who, in their time, were anything but mundane.

And anyone whose answer to this question is “the Nazis” clearly knows nothing about both history and Nietzsche. Not only is their ideology completely incompatible with his philosophy, but this also ignores his sister Elisabeth’s grafting her own cancerous growths onto his legacy after his mental decline and death, corrupting it with nationalist and anti-Semitic ideologies. This simplistic, uneducated belief ignores years of serious scholarship which has worked meticulously to excise these malignant additions from especially his later works. To conflate the two is to misunderstand both his ideas and their historical context.